Post Engagement Part II: Calling 9-1-1

In my last post-engagement article I wrote extensively about the post-engagement search and assess. If you haven't read that, I would encourage you to go back and check it out. Not to pat myself on the back but I think it's about the most thorough treatment of the topic out there. Today I'm going to talk about calling 9-1-1.

Part I | Part II

This article contains affiliate links.

I imagine that a massive cross-section of my readers carry firearms on a daily basis. I imagine that some smaller, but statistically still significant proportion of you also practice your technical firearms abilities regularly. You probably practice drawing, work to improve your speed and accuracy at various distances, and strive to reload and clear malfunctions smoothly and effortlessly. That's certainly laudable; very few gun owners go to such effort and I definitely commend you.

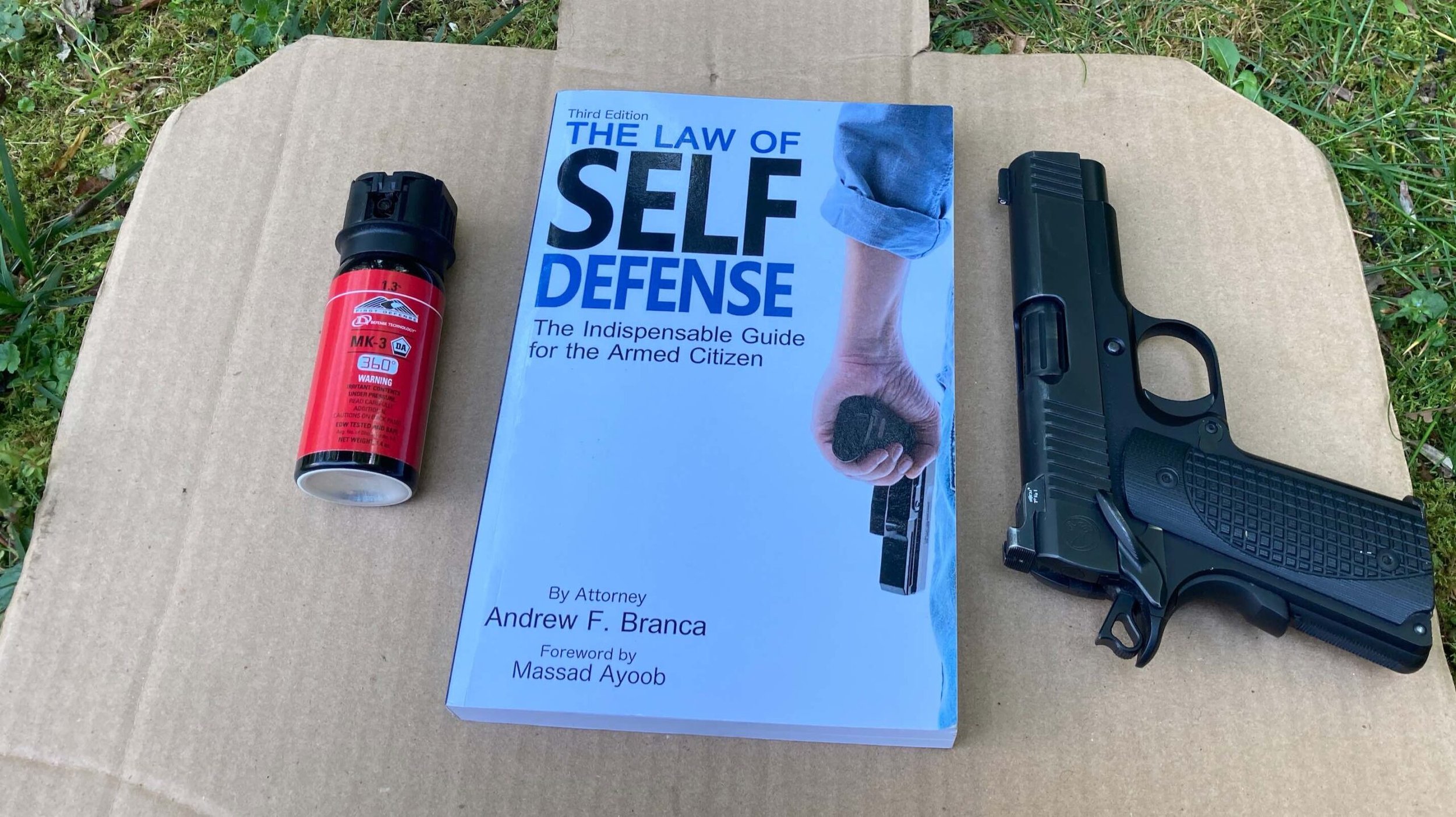

I have done a great deal of regular training (missing only three days of practice so far this entire year) and consider myself comfortable with the technical aspects of operating a handgun. Recently I have begun to realize that I don't spend much time practicing those crucial things that may or may not be necessary after a gunfight. For example, I was recently referencing something in Andrew Branca's excellent The Law of Self Defense, a book that I have recommended here before.

On a whim, I took a second to look up the section on calling 9-1-1. Mr. Branca recommends providing several elements of information to the 9-1-1 dispatcher. I've read the book but if you sat me down in a comfortable classroom at the beginning of this month, I couldn't have recited those elements to you. If you'd put me in a highly stressful situation and asked me to recite them? Quickly re-reading this section (pages 141 to 144) made me realize I needed to commit these elements to memory, and practice actually providing them, so I spent the first two weeks of June practicing my 9-1-1 call (along with drawing and a few other things). Here are some things I learned.

Getting the Phone Out & Dialing

In order to place a call, you will probably have to get your phone out of your pocket and into your hand. I alluded to this in my last dry-practice post, but it's worth reiterating.

In which pocket do you carry your phone? I carry mine in my right pocket, and I'm right-handed. That means that if my firearm is out, it is almost certainly in my right hand, necessitating withdrawing the phone with my left hand. Since I may or may not have fired, and my adversary may or may not be incapacitated. If you have the luxury of putting the gun away and retrieving the phone two-handed, cool. If not, you will want to have practiced this a few times. If you physically can't reach your right pocket with your left hand, you may want to consider carrying the phone on the left side (or vise-versa).

Why don't I just carry my phone in my left pocket? Trust me, there is a complicated set of reasons having to do with my pants and the other things I carry. And I don't want to have to relearn where all the crap in my pockets goes. So for now, I'm stuck with the phone in the right pocket.

Once the phone is out, you will need to dial. Again, there is a very good chance this will happen with your left hand. There are a few ways you can do this. If you have Siri or "Hey Google" enabled (I do not) you can verbally instruct your phone to dial 9-1-1, and I admit this might be a big benefit of these services (one of the very few, in my opinion). On newer iPhones you can also press and hold the power button and a volume button simultaneously to call emergency services. I recommend reading Apple's instructions and thoroughly understanding this feature. You can even practice using them because the most phones won't actually call 9-1-1 for several seconds, allowing you to cancel in the event of a mistaken dial.

If you're a Philistine (or security nerd) like me, you will need to be able to wake up the screen, hit the home button, then press the "Emergency" button, and do it all one-handed. Then you'll need to be able to press "9-1-1" and send. It's not as hard as it sounds, but I do have some advice. First, don't look down at the phone and dial everything. That can take your eyes out of the scene for several seconds. I like to look down long enough to dial one number, check the scene, dial one more number, check the scene, etc. You can find your own balance. Personally, enforcing the one number/reassess cadence keeps me from getting fixated on the phone if I misdial a key or whatever.

Other Handling Considerations

There are a couple other handling considerations you should keep in mind. First, you might want to set yourself up in a one-handed firing position before retrieving your phone. If your gun is still out that means there is still a possibility you may need it. Get in the best possible shooting position. Generally when firing strong-hand only I like my right foot forward and my body slightly angled in that direction. That gets a little bit more of my weight behind the gun. This is something that had never occurred to me until I actually started getting out and working through the mechanics of calling 9-1-1.

Second, are you using a flashlight? If so, you're going to have to make a decision to put down either the gun or the flashlight in order to hold the phone. Since the necessity of pulling a flashlight alongside a gun is very small this is pretty unlikely. Still, it's not the problem you want to be solving in the heat of the moment. In some cases the answer might be to put the light away, and in some cases it might be to put the gun away, depending on the situation.

Finally, there are other tasks you may need to complete after a deadly-force engagement. You may very well need to reload your pistol. You may be in an exposed position and need to move to cover or concealment, or just get out of an active roadway. There is at least some chance an injury occurred to your person, so you will want to ascertain your own intactness, and treat any necessary injuries. Do you do these things before or after you make the call? Do you do them while on the phone? I say probably not because of the chances of dropping the phone, but I can't imagine every possible scenario. Maybe that is the right answer sometimes. Regardless, 22:30 in the Walmart parking lot isn't the first time you should be thinking about these things.

Making the Call

Mr. Branca recommends providing five elements of information. The are your name, location (and location of incident, if different), the facts that you were attacked, you were in fear for your life, and that you had to defend yourself, followed by a request for police and an ambulance. For a more thorough explanation of why each of these is important, I strongly encourage you to read The Law of Self Defense for yourself.

During my dry practice sessions I practiced getting the phone out, dialing 9-1-1, and the going through Branca's recommended elements. I tried the most variety in providing the location. I thought through the places I most often am - the two grocery stores at which we shop, the ATM I use most frequently, my preferred gas station, etc. Using my car and patio furniture as a prop I was able to practice describing, "...in the front of the store, at the registers, near register number 7." or "in the parking lot between a red F-150 and a blue Buick sedan."

In some instances I also practiced describing my appearance. I do not want to be shot by police. Though this veers from Branca's recommended advice, friendly fire...isn't. At first I found I didn't remember any of the necessary elements and needed prompting. So, I made a script card that I used to guide my imaginary 9-1-1 calls. This listed the elements above, and just served to make sure I got in the habit of providing them in order. Staying in order helps to ensure you don't forget anything and that you get the pertinent details out efficiently.

Parting Shot

I know this isn't the most exciting topic. I further realize that I am probably not doing everything perfectly or as good as I should. But I'm doing something and I feel that something is necessary. Calling 9-1-1 after a shooting is really, really important. If it's important, you should practice it. If you don't like the way I do it, find your own way to do it, but practice something.