I am a big advocate of the Every Day Carry (EDC) flashlight. I have carried a flashlight on my person in some form or fashion for over a dozen years. There are a number of reasons to recommend the practice of carrying an EDC flashlight. This post will explore some of these reasons, and open a series of upcoming reviews of popular EDC flashlights.

Why Carry an EDC Flashlight?

In case you aren’t convinced of the necessity of carrying a flashlight on your person, let me attempt to persuade you. The simplest, and still the best, reason I’ve ever heard given for carrying an EDC light: “it gets dark every day.” Daily darkness provides ample opportunity to use a flashlight.

Day-to-Day Utility: Unlike a concealed firearm, a flashlight is something you will find a need to use almost every day. Having a resilient, handy light source has obvious utility. The uses of a small, lightweight flashlight are innumerable, but may include: finding dropped items, looking for items in dark recesses of a closet/drawer/under the bed, or lighting a path when walking your dog.

Performing small tasks (or rendering tasks like these easier) is the primary use-case for my EDC flashlight, and probably will be for yours, too. There are also more serious reasons to carry an EDC flashlight.

Emergency Use: Sometimes the lights do go out. Over the past year I recall at least three power outages that I’ve personally experienced. One was at my home. This was no big deal at all; I am familiar with my home and have plenty of alternate (battery powered) light sources available. The other two were a little different though. Both happened while I was staying in hotels. Coincidentally both occurred in the same city, though in different hotels, and separated by several weeks.

In both of these cases there was no true emergency. In the first case the outage happened during the day, while I was at work. When I got off the power was still out so I went and had a leisurely dinner. But the time I finished up, the power was back on. The other instance happened around 8 PM, after I’d settled in for the night, but before I went to sleep.

If you’ve never experienced a power outage in a hotel, it’s a mildly unsettling experience. You know that you are surrounded by other guests, most of whom are probably far less prepared than you are. In that instance I had two flashlights with me (the one I carry on my person, a larger light I carry in my luggage) in addition to my phone. In both cases I knew I was well prepared and, if needed, able to get myself and others safely out of the hotel.

Defensive Utility of an EDC Flashlight

A lightweight, compact flashlight can be used as a defensive tool. A light can help you investigate noises without having to approach them too closely. Shining a light around a darkened parking garage can serve multiple purposes. First, it allows you to see people who may be attempting to conceal themselves in the shadows. Second, it very likely makes you look more alert and less vulnerable. It may even make you look like a cop; in either case, it makes you a less attractive victim.

If you are approached or attacked, a flashlight can serve as a weapon. The judicious use of a high-powered beam of light can blind and disorient an attacker. This is especially true if his eyes have been adjusted to low light. This can create a window of time to facilitate escape from the area. While a flashlight would never be my first choice as a defense tool, flashlights do enjoy two immense benefits. They are extremely approachable and universally legal.

The flashlight is an inherently approachable tool. Unlike a knife or gun, the flashlight is not perceived as a weapon. Like a knife, it is a tool that nearly every human has some familiarity with. Everyone has used a flashlight when camping or pursuing some other outdoor activity. Most of us probably use (or at least look for) a flashlight when the power goes out.

Occasionally someone will exhibit mild surprise when I pull out a flashlight. Not because of the light itself, but because of the fact that I’m carrying one. Still, no one is offended or frightened by it, and they usually end up thanking me for helping them locate whatever they were looking for.

Just as (or perhaps more) importantly, flashlights are allowed literally everywhere. My EDC light has accompanied me into federal buildings, onto airplanes, to concerts and museums. While a gun, knife, and even pepper spray are prohibited in many of these venues, I’ve never – not even once – been asked to surrender my flashlight.

EDC Flashlight Selection

With the wide variety of perceived use-cases for EDC flashlights, there is a booming market to support the demand. Flashlights are optimized to suit nearly every real or perceived need, preference, and taste. I’m going to discuss my own evolution with EDC flashlights, then some selection criteria.

I’ve struggled with EDC flashlight selection for a while. There are a million choices with a bewildering array of options. I’m a pretty avid follower of Grant Cunningham, and his recent, excellent articles on carrying a knife and a flashlight (Part I, Part II) got me thinking. They kicked me into gear and got me a little more serious about light selection.

I began EDC’ing a light in around 2007. It was a little Photon keychain light. I carried this for several years before being introduced to the world of “real” EDC lights. Before this I had no idea there was a middle ground between a tiny keychain light and a big, full-bore tactical light. I do now, and that middle ground is vast.

Stepping up gently, my journey carried me next to single AAA lights. Since 2010 or so I’ve carried a variety of lights from Fenix and have mostly been happy, but most of these have left something to be desired. Because of the AAA’s limited capacity the batteries are life-limited. Additionally, a single-AAA light can’t burn as brightly as a battery with more capacity. And it turns out the single-AAA’s biggest advantage – it’s tiny size – is also a disadvantage. For want of space, the very small AAA lights are lacking some features found in the bigger models.

The two lights that I have carried through the bulk of my light-carrying life are the Fenix LD01 (no longer produced) and the Fenix LD02. Both are tiny and completely pocket-carryable. Both are (were) high-quality, durable, water-resistant lights. Both offered a High, Medium, and Low mode…and that’s it. When I finally began researching AA- and larger cell flashlights, the world began to open up to me.

I began to realize the vast array of functions available in a simple flashlight. Unfortunately, this also caused me some problems. These problems were good ones to have: the raft of features available on larger lights can be extremely confusing. I began reading reviews, watching YouTube videos, and – not unlike most people in this genre – ordering more flashlights than my significant other was thrilled with. After a while I began to understand the various features offered in the ponderous EDC flashlight market. Once I understood these, I began thinking about what I wanted in a light. But there’s a rub…

Mission Drives Gear

I’m also what many might call a “tactical,” or self-defense oriented guy. Most of the self-defense world tells me I need to carry a light with hundreds of lumens and a single mode. I’ve heard/read, “if the light has more than one mode, it’ll end up in a mode you don’t want it in,” or words to that effect more than once. I’ve thought a lot about that statement. I generally disagree with it, but I’m still swayed by it.

My disagreement is this: first, I use my flashlight almost every single day. Most of those uses call for way less light than a tactical Surefire (or similar) produce. If I have only a single mode I have a tool that is way less capable than the single AAA light buried in my pocket.

Secondly, the light is about as likely to be used in a fight as a spare magazine. That is to say, the possibility of using it is vanishingly small. Tom Givens’ considerable body of gunfight data would back me up on that. Even though most of his accumulated shootings have occurred during hours of darkness, they haven’t occurred in actual darkness.

With that in mind, I want a light that will function in the fighting role if needed without sacrificing all the day-to-day functionality a flashlight offers. While as I mentioned, I’m still slightly swayed by the hardcore self-defense guys, but I’m more swayed by guys like Grant Cunningham. After reading his advice, my goal became to find a light that is optimized for the guaranteed scenarios but still suitable for the outliers.

With awareness of the various features available, competing priorities of a.) wanting a light that suffices for day-to-day use with multiple modes of intesity, and b.) functions in the self-defense role with an easy-to-deploy “HIGH” mode of intensity, I began to develop my own set of criteria for a light. These probably aren’t exactly right for you. They are certainly not right for everyone. But they should give you an idea of how to develop your own criteria.

So, Maybe Carry Two Lights?

No. I get it – the siren song of one light that is ideal for self-defense purposes and another optimized for normal use is alluring. But it’s an inelegant solution. It’s inelegant because it forces me to carry redundant items. It also forces me to carry an item that will almost certainly never be used for its intended purpose (the self-defense light).

Also, I have limited pocket space. I carry a decent amount of crap on me. I’m not going to double up on one item when I should be able to find one that meets all (or at least) most of my needs and wants.

My EDC Light Criteria

My criteria for “the perfect” EDC light are listed here. These aren’t in any particular order, because the perfect light would satisfy all of these criteria. Unfortunately, I’ve yet to find a light that does. Here they are:

- Tail switch featuring:

- programmable to access “HIGH” mode instantly

- the option of “ON” and momentary “ON”,

- protective ears/tail stand

- Powered by a single battery (preferably AA)

- Multiple Modes, including:

- high, low, and <1 lumen firefly,

- No or removable strobe function,

- Optimized Form Factor,

- Durable and water-proof/resistant.

- Tail switch featuring:

Let’s look at each of these criteria a little more closely.

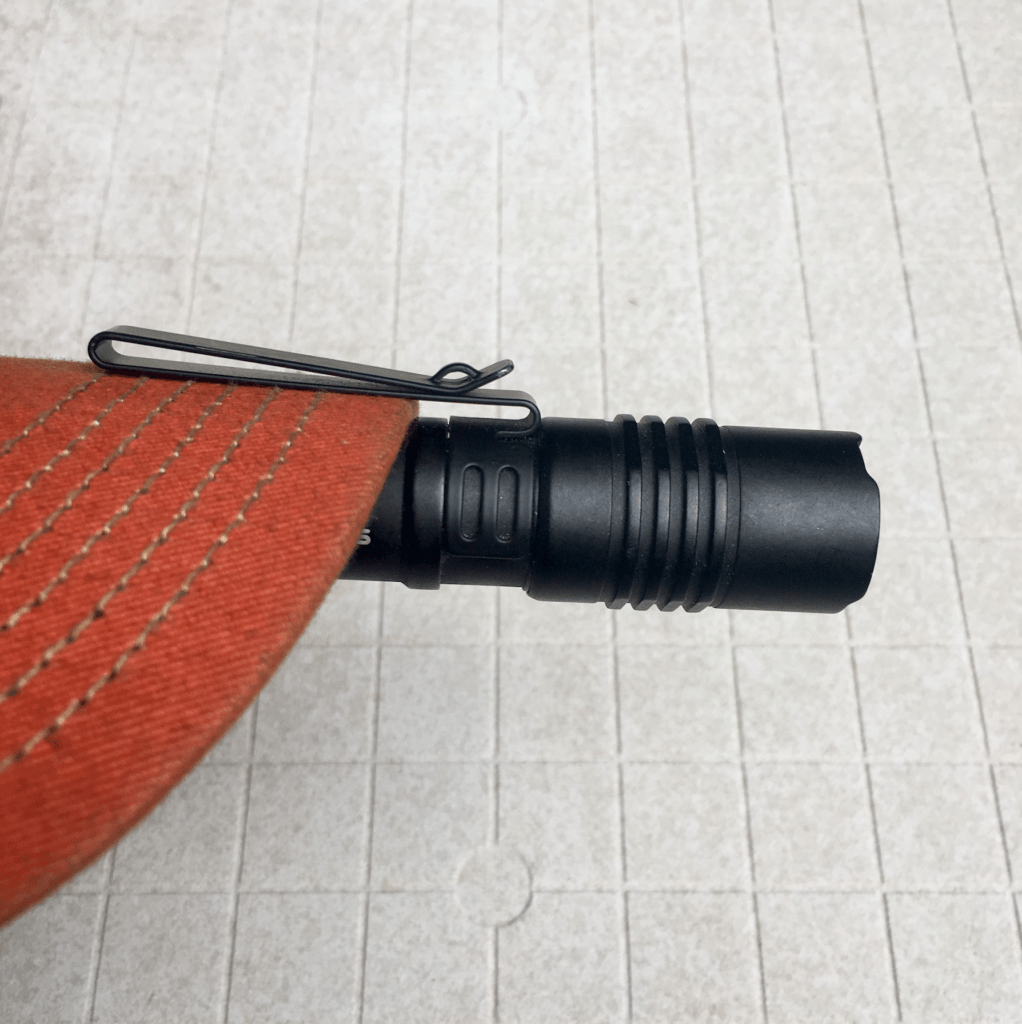

Criteria 1: TAIL SWITCH

A tail switch – in case you’re not an EDC bro – is a “clicky” rubber switch on the rear of the light’s tube. This allows you to hold the light with all four fingers in an “ice pick” grip and actuate the switch with your thumb. A tail switch works well with most self-defense methodologies, and is generally pretty easy to use.

There are several ways to turn on a flashlight. Some lights require you to twist the head or bezel, like the old, now-discontinued Fenix LD01 I used to carry. My main problem with this mode is that it’s very difficult to turn the light on one-handed. It also isn’t super positive; with a switch the light is either “ON” or “OFF”. With a twisty head, turning the light to “OFF” involves unscrewing the head until the light turns off. If you don’t unscrew it quite enough, pressure against the head of the light in your pocket can turn the light back on. Screw it off too much and the light loses water resistance. Screw it off much more than that and you risk your light coming apart in your pocket.

Some lights have a push-button switch near the head. Again, I have a couple problems with these. Most importantly, the button can be hard to find in the dark – exactly the time you need to be able to find them. Finding a tail switch is easy. It will be on one end or the other of the light. Finding a switch on the light’s head…well, there’s 360 degrees of head there. The switch doesn’t stick out a whole lot because if it did it would either a.) get broken, b.) get turned on in your pocket a lot, or c.) both.

Since I want my light to be adaptable to self-defense, a tail switch makes the most sense. It can be operated one-handed. There’s a low probability of missing the switch. Switching the light from “OFF” to “ON” and back again is positive.

Criteria 1a: Instant “high” mode

There are also some sub-factors that I would like in a tail switch. The first is that the switch be programmable to access the “HIGH” mode instantly. My reasoning is this: if the light is used for general utility, I have time to find the mode that works best for the situation. If the light is used in extremis I don’t have time to toggle through multiple modes. I want the light to come on in the best possible mode for self defense, and allow me to adjust down from there.

There are a few ways this may be accomplished. One is to make the light programmable. A great many of the EDC lights on the market nowadays are programmable, allowing the user to select the order in which the modes are accessed, and add/remove modes. Another way to accomplish this is to give the light a “memory.” This means that the tail switch accesses the last mode used. This is OK, but relies on the user ensuring that the light is always reverted to “HIGH” mode anytime the light is used in a lesser mode.

Yet a third way to permit instant access to “HIGH” mode is to add a button on the bezel. With this arrangement the tail switch is used to power on the light and the bezel button is used to cycle through modes. A secondary mode button and the ability to program the light is the absolute best-case scenario.

Criteria 1B, 1C: Momentary ON, Tail StanD

The next two sub-factors are probably less important, but extremely desirable. The first is a “momentary ‘ON'” from the tail switch. If you aren’t familiar, this means depressing the tail switch partially, activating the light. The light is extinguished as soon as you release pressure from the switch, allowing a quick “momentary” use of the light.

Finally, a tail stand. A tail stand consists of protective ears or shrouding around the tail switch. This protects the switch from being accidentally depressed while in your pocket. The light being on in your pocket needlessly drains your battery, and some lights can get extremely hot if left on for long periods.

A tail stand, as the name implies, also allows you to stand the light up on its end. Though its usefulness might be debatable, a tail stand is a feature that I really, really dig. When you stand the light on its end, light is directed at the ceiling. This light is then reflected, providing good, diffuse light over an entire room. This might not seem like a huge deal until you need to provide general lighting in a room.

Criteria 2: Powered by a Single Battery

Battery selection is a huge topic unto itself among flashlight guys. There are guys that will debate AA vs CR123, AA vs 14500s, alkaline vs. lithium, throwaway vs. rechargeable, and on and one. I want a light that is powered by a single battery, preferably a AA battery.

Form-factor is a huge reason for this. I’m not going to carry a light that takes multiple batteries; they’re just too large (I’ve tried). If the batteries are stacked end-to-end, the light is too long for me to pocket carry. If batteries are side-by-side the light is too fat to carry.

Settling on AA as the ideal battery size also has to do with form-factor. A AA battery holds almost twice the energy of a AA without requiring an appreciably larger housing. The CR-123 battery holds considerably more energy still, but is a massive leap up in diameter from the AAA. Additionally, AA is one of the most common batteries in existence. I have plenty at home, they are (relatively) inexpensive to purchase, and I should be able to find some in an emergency.

I will weigh in on rechargeable vs. throwaway batteries. As much as I dislike throwing batteries away, I won’t commit to a rechargeable. When my battery runs out I want to grab another one and keep on trucking. Admittedly some lights have an elegant solution: flashlights utilizing the 14500 rechargeable can often be used with AA batteries, too. They aren’t optimized for use with AAs, but AAs will work. Still, that’s not quite enough to sell me on rechargeable batteries.

The problem with wanting an AA light…there just don’t seem to be that many on the market. Manufacturers seem to mostly make lights for AAA or CR-123 batteries.

Criteria 3: MODES

This one focuses on the day-to-day utility of the light. There are a TON of modes you can ask for in a flashlight. All I really care about are functional modes for day-to-day life. Ideally that would include HIGH and LOW settings, along with (ideally) a “Firefly” mode. This allows you to choose the appropriate amount of light for, say, looking for the remote under the couch, to scanning the yard after you’ve let the dog out for the last bathroom break of the night.

High and low modes are mostly self-explanatory. However, I do have one point of clarification on the “high” mode. I’m not interested in a quadruple-digit lumen count. Though that power may be nice in the extreme outlier situation, extremely high lumen counts seem to bias the entire light toward higher numbers. Although I may employ this light as a self-defense tool, it’s primary purpose is as an every day tool. I think I’d be happy with a HIGH in the neighborhood of 200-300 lumens, and a LOW between 15 and 30.

Two modes that completely fail to interest me are “medium” and strobe/SOS. I have lights with “medium” modes, and I almost never use them. I typically either need a lot of light or a little light.

“Firefly” mode may is not self-explanatory. Firefly is a very low mode that allows you to see in pitch darkness without totally blinding you, waking your sleeping significant other other or child, or running your battery down exorbitantly. Firefly mode allows you to read without having washed out portions of the page. A firefly mode of 1 lumen or less is incredibly useful.

Criteria 4: Form Factor

There are a multitude of little factors that could go into form factor. I will attempt to list a few things that really matter to me.

Size: The size of an EDC light should be optimized for pocket carry. My ideal specifications for size/weight are: between 3 and 4 1/2″ in length, maximum diameter no more than 0.80 inches, weight no more than 2.5 ounces.

Pocket clip: a pocket-carried light should have a pocket clip, or the option for one. Bonus points for lights that offer a reversible clip that can be used to clip the light to a hat brim for use as a headlamp.

Knurling: I’ve worked with some smooth lights, and knurling definitely makes a difference in your ability to hold on to the light. This is especially true if using the light under stress, or while attempting to manipulate a handgun.

Anti-Roll Flats: These are simple flats milled into the thickest portion of the light (generally the bezel). Flats give you the ability to set the light down on an unlevel surface and without worrying (too much) about it rolling away. This feature is optional if the light has a pocket clip, but still demonstrates attention to detail.

Criteria 5: Durability and Water Resistance

There isn’t a whole lot to say here, so I combined these two categories. These criteria didn’t initially play that big a role in my search for an EDC flashlight. Not because they aren’t important; they are. Rather, I didn’t prioritize them because I thought these were more or less standard features, but I know better now.

The bottom line: I don’t need the toughest, most rugged, hard-use light science can produce. I want a light that can survive the abuse of living, day-in and day-out in my pocket. I want a light that can stand being dropped occasionally, because I eventually drop everything. And I want a light that can take being dropped in the river or the toilet because…well, refer to the previous sentence.

Wrap Up

In this post I talked about the reasons you should consider carrying an EDC flashlight: day-to-day utility, emergency use, and usefulness as a self-defense tool. I talked about my journey in the world of EDC flashlights. Finally, I just spent way too many words explaining my light selection criteria. So where does this go from here?

I’m going to start reviewing flashlights that come close to meeting my criteria. Even though I shouldn’t, I’m going to give you a spoiler right up front: I still haven’t found one that meets all the criteria and I’m currently working with a compromise solution. Still, there are some pretty good lights out there that may work for you, or may not. Hopefully these upcoming reviews can help steer your decisions in the right direction.