Today I write to you as a a fully-credentialed, practicing paramedic. This post is going to talk about how I got here, and the road to becoming a paramedic. I’ve written about this a little bit before, when I had just started school. There seems to be a lot of mystery about becoming a paramedic, so today I’d like to go into a bit more depth. Here’s my experience. Yours might be a bit different.

School

I attended a vocational program. Very soon paramedics will be required to have a two-year degree. For now you can still attend a certificate program like I did. I went to school every Monday and Wednesday evening from 6 PM to 10 PM, and every-other Saturday from 8 AM to 5 PM. For the paramedic portion I only attended for 13 months. Prior to enrolling in the paramedic program I had to become an EMT, which was another 4+ months of school. I was in school from January, 8 2020 until June 21, 2021 – right at a year and a half.

Added into each school day was half an hour of travel each way. I’d eat dinner at 5 PM, get in the car, then get home around 10:30. That’s not the worst thing in the world but it certainly wears on you. I became really frustrated with it at about the 1-year mark. Those last six months were challenging from a motivation standpoint. Simultaneous with school was work (everyone in my program also worked somewhere) and clinicals.

Clinicals

The hardest part about the program was the clinical portion. Clinicals were performed on your own time. Even though I work at EMS I couldn’t count work days as clinical experience (aka: no “double dipping”). And, it should probably go without saying, clinical shifts are completely unpaid. I completed the following clincials:

- 1x – 12 hours Infusion clinic. Infusion is an outpatient clinic where people show up to receive IV drugs on a regular basis.

- 1x – 8 hours Operating Room. The primary purpose of the OR is to get intubation attempts. I got 3 attempts, and was allowed to observe a couple surgeries.

- 1x – 12 hours Intensive Care Unit. My ICU experience wasn’t super noteworthy good or bad.

- 1x – 12 hours Respiratory Department. Respiratory was my craziest day – I got to participate in a “stat” C-section delivery, help with some conscious sedations, etc.

- 1x – 8 hours Pediatric Clinic. Sounds cooler than it was. This was essentially just a doctor’s office. I basically just got vitals on kids as they came in for visits with their pediatrician.

- 6x – 12-hours Emergency Department. This was fantastic. I got to do normal ER stuff (start IVs, draw blood, ECGs, etc.). More importantly I got to know our ER nurses and docs, and learn how our ER works.

- 20x – 12 hours on Ambulance. Obviously, right? Though I actually ended up doing about 25 of these rides to get all the required skills.

- 1x – 8 hours with the Community Paramedic. The Community Paramedic visits “frequent fliers” to reduce their 911 calls, delivers meds to shut-ins, and that sort of thing.

Clinical Skills

During all these clinicals we had to get a number of quantifiable skills. In total the skills we had to practice on live humans in clinicals were:

Assessments, and a ton of them. I far exceeded all of the categories with the possible exception of OB patients. We had to assess the following patient populations:

- 20 pediatric patients,

- 40 adult patients,

- 40 geriatric patients,

- 2 each of the following:

- trauma patients,

- psych patients,

- medical patients,

- chest pain patients,

- respiratory distress patients,

- syncope patients,

- abdominal patients, and

- patients with an altered mental status.

Next, we had to perform a number of interventions, including:

- 30 IV access (80% success rate or better)(these were easy to get; I probably left school with several times the minimum),

- 20 each 4- and 12-lead ECG with interpretation (not including asystole or normal sinus),

- 50 airway managements (positioning, OPA/NPA, BVM un-intubated patients, etc.)

- 8 advanced airways (BIAD, intubation, etc.), and

- Administer the following medications:

- 20 medications via IV/IO (also easy to get, I probably had a couple hundred IV med pushes),

- 4 medications orally, sublingual, or intranasal,

- 4 medications via nebulizer (hard to get during COVID because this is a “droplet producing” procedure), and

- 3 transdermal medications (i.e. nitroglycerine paste)

The hardest skill to complete was the required 20 “ALS team leads.” In a nutshell I had to lead the call. I had to assess the patient, come up with a working diagnosis, and a treatment plan. More than two prompts from my preceptor (the medic riding with me) and I failed that call. It took FOREVER to get my 20 team leads. I was a proverbial “white cloud;” when I went in for clinicals the calls just stopped. I ended up working somewhere around 60 extra hours of ambulance clinicals to get my team leads.

Additional Certifications

Believe it or not, there are also a ton of other certifications we have to maintain. You’d think these things would be baked into the paramedic curriculum, and to be honest they pretty much are. But NAEMT has to make money somehow, so we get to maintain their certifications. The additional “alphabet soup”-cards we came out of class with are:

- BLS – Basic Life Support (aka CPR),

- ACLS – Advanced Cardiac Life Support,

- PALS – Pediatric Advanced Life Support,

- GEMS – Geriatric Emergency Medical Service

- AMLS – Advanced Medical Life Support,

- PHTLS – Pre-Hospital Trauma Life Support

- TECC – Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (the civilian equavalent of TCCC), and

- PTEP – Psychological Trauma in EMS Patients

Testing

Testing seems like it would be fairly straightforward but it’s not. Regardless of where you live, becoming a paramedic will probably require several tests.

Scopes/Oral Boarding

First, I had to pass what is known as “Technical Scope of Practice.” This is the most daunting part of the process. Each candidate has to sit in front a board and talk through various scenarios. My board consisted of my agency’s medical director (a physician), my agency’s training officer and two Field Training Officers, two flight paramedics from another agency, and my paramedic course’s program director. This was a pretty daunting group to sit in front of but I passed with flying colors.

Additionally, at any agency you want to work at you also have to pass an oral board. Fortunately – since my scopes were staffed by folks from my agency – they also counted toward my oral boards. I didn’t have to sit through them again to move up to a paramedic position at my agency.

Final Exam

Next, I had to take the final exam to graduate my class. This was a 200-question, timed, computer-based test. I passed this with a 91%, so no complaints there. Once the final exam was complete I was allowed to sign up for the next testing event…

State Test

Next, I had to pass a state test. This is a proctored test given regularly at any approved testing facility. I just had to decide on a facility that met my needs in regards to proximity and time-frame. I ended up driving to a center about three hours away, exactly one week to the day after my final exam. As soon as this test was passed I was officially a paramedic. I could begin working as a “provisional paramedic” at my agency. Oh, and this test isn’t free. I had to pay $65 to take this test.

National Registry Test(s)

Finally, I had to take two tests for the National Registry of EMTs (NREMT). Being “nationally registered” isn’t required at my agency. However, it is required for certain jobs, like flight paramedic. It also makes transferring your credentials state-to-state a little easier. And it looks great on a resume, but it doesn’t really guarantee you anything. The two tests were a cognitive exam and a “psychomotor ” (hands-on, skills) exam.

The cognitive test required traveling two and a half hours from my home to a testing center. The computer-based test is adaptive. It gives you a minimum of 70 questions, then adds question depending on which ones (and how many) you answered incorrectly. I passed it in 79 questions.

The psychomotor test is a little more difficult. I have to drive three hours from my home, to another state, and spend the night. I have to be at the facility at 8 AM, and expect to be there until about 3 PM. This test consisted of identifying ECG rhythms, demonstrating skills (against very specific checklists), and doing verbal scenarios.

This set of tests cost an additional $152, over 500 miles of travel and a hotel stay.

And That’s It! Right?

Well, yes and no. I’m a paramedic. Above and beyond that I’m a Nationally Registered Paramedic. So there’s that, but as they tell you in school, “this is just the beginning.”

You can set the bar as high as you want for yourself, but there are some very clear ones I need to pass now. First I have to pass my agency’s Field Training program. Until I’m a “released” paramedic I have to ride with a Field Training Officer (FTO) whenever I work. I don’t really mind; that guarantees I’m with a highly-qualified medic for a while. It will be nice to be a “real” paramedic, though.

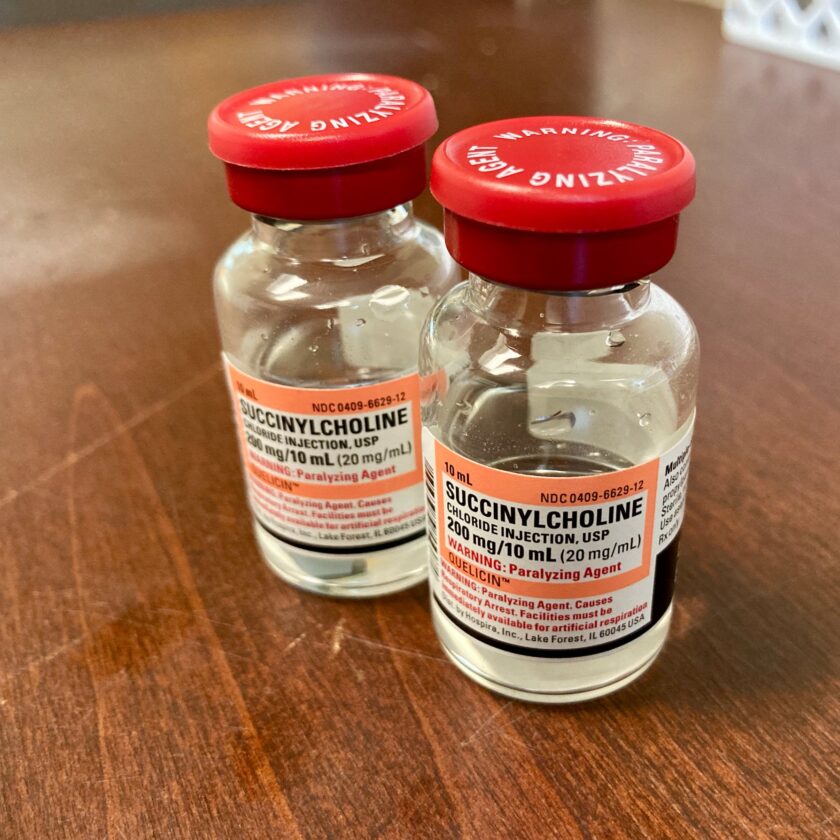

And then there’s a bunch of other little hurdles. For example, in order for me to conduct Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI)† at our agency you have to be a “RSI Medic.” Even though the state says I can RSI, our agency requires that you already have eight intubations and attend an agency class on RSI protocols. RSI is not a very oft-used skill so this isn’t terribly important, but I wouldn’t like to be able to do it should the need arise.

Anyone who has ever worked in healthcare also knows about Continuing Education. As a NREMT Paramedic I have to do 60 hours of continuing education (“con ed”) every two years. And it’s broken out into specific types of con ed: 3.5 hours of respiratory, 8.5 hours of cardiac, 3 hours of trauma, 8.5 hours of medical, 6.5 hours of operations, 15 hours of state-specific stuff, and 15 hours of individual training. It takes some effort to stay certified on all this stuff. And then there are all sorts of other certifications out there: Critical Care Paramedic, Flight Paramedic, Tactical Paramedic, etc, etc.

Was it All Worth It?

Was it worth all the effort put into becoming a paramedic? Let’s look at two metrics. The first is financial worth. The second is intangible value.

Financially Worth It?

Financially, absolutely not. In fact, I think becoming a paramedic is a terrible financial investment. My class was free because of my affiliation with the local rescue squad. I had to pay for my book, background and drug tests, exams, and a couple other minor fees. I’m guessing I paid around $1,200 out-of-pocket. Not bad for a year-long school. My time investment was huge, though. I spent about 1,500 hours getting here. I was stressed and tired through a bunch of it. So what is the financial return on my investment in becoming a paramedic?

I now make a little less than $16/hour (even with a brand new, 2% COLA raise). Let’s look at my 18-year-old niece as a counter-example. My niece works at Chic-Fil-A in the same area I work in. She has worked there less than two months. She has received three raises and now makes $18/hour. That’s right – I make $2/hour less than my niece (and don’t forget: she gets free meals!). Sure, Chic-Fil-A is at the higher end of the pay scale, but they aren’t the only fast-food joint paying more than the starting pay at my agency. I would absolutely NOT recommend becoming a paramedic for the pay. There are probably any number of other vocational programs with substantially higher earning potential. I doubt that’s a popular opinion but it’s 100% the truth.

Worth it in Other Ways?

So why bother with becoming a paramedic? It’s worth it in other ways. I have found that I love serving my community. Sometimes they’re dicks to me. Calls can be dangerous (I hate working wrecks on the interstate). Very often the person probably could have just driven themselves to the hospital. But I’m humbled to be an employee of the Citizens of my county and I’m proud of my accomplishment. I’m also getting something else out of it: experience. If you want to be good at first aid you should probably do a bunch of it. I’ve put myself in a position to get experience treating illness and injury…and I love it!

Will I work as a paramedic long-term? Honestly I don’t know but overall I would say it has been worth it. Whether I continue to work as a medic full-time or not I will definitely maintain my certification.

†Rapid Sequence Intubation (or Drug Assisted Intubation as it is becoming known) is an uncommon procedure used when airway compromise is imminent. The patient is sedated, then chemically paralyzed (to prevent gagging/vomiting), then intubated.