Welcome to EMS Stories! Today I would like to talk about a call that highlights the importance of advanced directives like the Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) form.

EMS Stories

This post begins a new series here at Swift | Silent | Deadly. EMS Stories will share some (sanitized) stories from my experiences working as a paramedic. I know I have a few readers who are medics with many years of experience. They probably won’t find this stuff all that interesting. The rest of you very well might. Very few people have any idea how their local EMS system works or what goes on inside it. I hope to give you a little bit of that while it’s still new and novel.

This segment won’t become a place for war stories, and it won’t be to make me look good. I hope to share stories that can teach my readers something. This may be a deep, long-running series…or it may end up with just a handful of installments. Either way, I hope these stories can teach something. Let’s get into today’s EMS story.

The Call

The call was for an “emergency sick person,” in the parlance of our dispatch system. We arrived on scene at a nice, well-maintained home. Upon walking in we found a hospital-style bed in the living room. This isn’t terribly unusual; oftentimes when a aging parent is very ill families will move mom or dad back in. Due to the amount of medical equipment necessary it is often easier to turn the living room into a makeshift hospice room than to move them into a bedroom.

A very sick, very old woman was sitting on the edge of the bed. I knelt beside her, introduced myself, and asked her how she was doing. She told me that she had stage 4 cancer and was dying. She was 93 years old and had just been discharged from a large oncology ward the day before. I asked what made her call 9-1-1 today. She told me that she had been vomiting all day. She was obviously in tremendous pain and on a generous regimen of opioid pain medications which often produce the side-effect of nausea.

I asked my standard battery of history questions and ascertained that she was alert and oriented and capable of making decisions regarding her own healthcare. Satisfied that she was we asked her what she would like to do. With a resigned voice she said, “I guess I have to go back to the hospital.” She further added, “I wish the lord would just take me. I just can’t go on like this.”

The Do Not Resuscitate

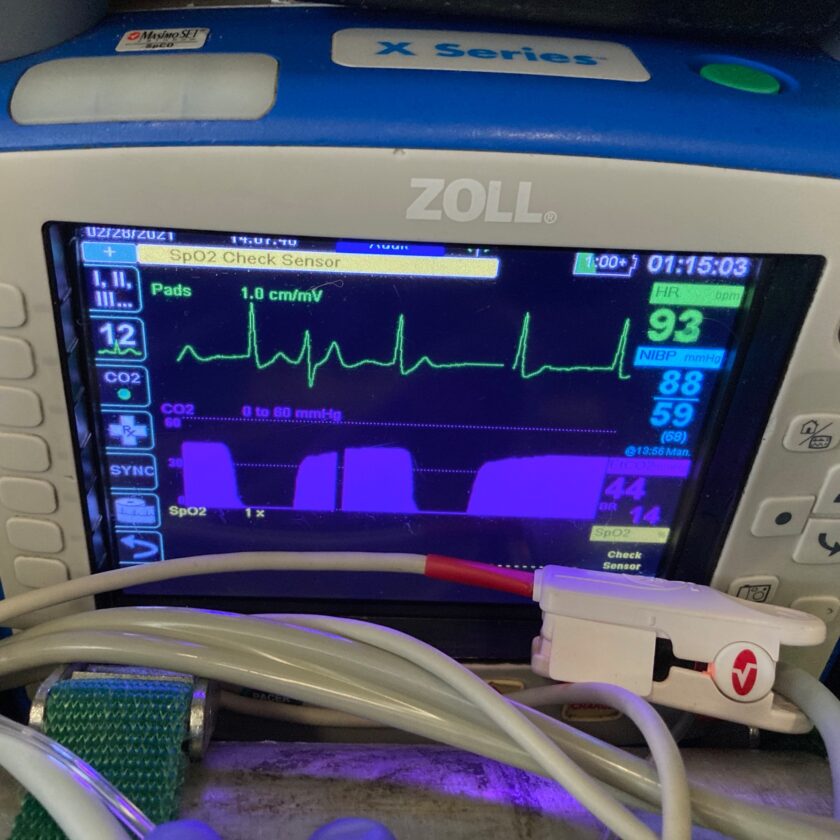

At this point we transferred the patient to the stretcher. We wheeled her to the back of the ambulance and began loading her. As soon as we were in the ambulance the patient lost consciousness. Losing consciousness is a huge deal. It’s not like the movies where people get knocked out and it’s just fine. Losing consciousness can mean you’re having a brain bleed, you are have dangerously low blood sugar, your blood isn’t carrying sufficient oxygen, your heart isn’t moving enough blood, or a number of other potentially fatal conditions.

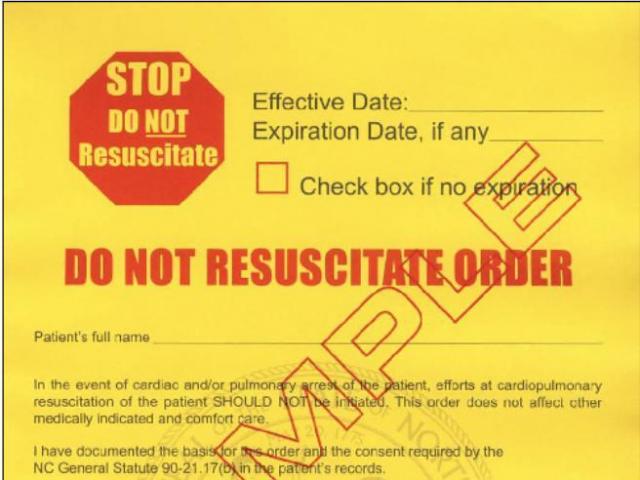

My much-more-experienced partner and I looked at each other: was the patient about to “code”? Fortunately her eyes opened and she spontaneously regained consciousness. At this point I noticed a purple bracelet on her right wrist that said, “DNR”. I immediately understood that this was placed on her during her recent hospital stay. This meant that she had a valid Do Not Resuscitate as little as one day ago (when she left the oncology ward). The bracelet means nothing, legally, however. We have to have the actual document – the so-called “golden ticket” – in hand.

Seeing that the patient might be fairly critical I told my partner I was going to run back in the house and ask the family about the Do Not Resuscitate form. If this patient went into cardiac arrest en route to the hospital I didn’t want to perform interventions that she didn’t desire.

The Conversation

I walked back inside and asked the patient’s daughter, “I’m sorry to bother you again. I noticed your mother’s DNR bracelet; do you have the actual document?”

At this point the call suddenly and unexpectedly turned confrontational. “No I don’t,” she barked sternly. “I don’t know where that came from! She must have done that behind our back when she was at the hospital!”

“Ma’am,” I began, “it is always a possibility that a patient’s heart could stop on the way to the hospital. We just want to be prepared for that possibility. Without the DNR document we are legally obligated to give her the full scope of treatment, which is usually quite traumatic.”

“That’s fine with me!” she said sharply, ushering me to the door and slamming it behind me.

I walked back to the truck in utter disbelief. We started en route to the hospital, a good 30-minute transport. Fortunately the patient didn’t code. Still, I couldn’t believe the attitude the daughter had around the DNR and her mother’s wishes. Let me explain.

This was the first time that I’ve seen this, but I’ve seen it since. It usually stems from the family failing to accept the reality that someone they love will die. Rather than accept that reality they will put their loved one through a tremendous amount of pain to prolong their life for a few more days or maybe weeks. This is also often because families have no clue about the nature of treatment for cardiac arrest.

The Reality of Resuscitation

Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) is incredibly traumatic and undignified. Generally it’s going to work something like this: your loved one will be thrown in an ambulance. Their clothing will be cut off. The back of the truck will be occupied by a couple of paramedics and usually a couple firemen. Sometimes as many as a dozen people – cops, firemen, medics, supervisors – might be milling in and out if this happens at home.

We will try to establish an IV, but if we can’t get one, we’ll drill a needle directly into the your mom or dad’s shin bone (video) to allow medication administration. Your loved one might be shocked, resulting in full-body convulsions (somewhat accurately portrayed on TV).

All the while, CPR will be performed. It can break ribs, sternum, bruise lungs, and cause other trauma. As CPR is performed a paramedic will attempt to intubate your family member. A variety of potent medications may be administered during a cardiac arrest, some of which can remain in circulation for days to weeks.

While the chest of your naked loved is being compressed, the firemen and medics will be shooting the shit and catching up with each other. They might even be joking around. To outside observers it seems at best too casual, and at worst callous. This is our profession, though, and this is just part of our natural stress-relief mechanism.

Long story short: resuscitation ain’t pretty. Even worse, it often doesn’t work.

This Applies to YOU!

Unfortunately the results of a full resuscitation attempt are far from guaranteed. I have worked in EMS for a little over a year now. I’ve worked a number of cardiac arrests. I’ve gotten pulses back a few times. However, I have yet to have a single patient ever leave the hospital, except to be discharged to hospice. All my cardiac arrest patients so far have died, just hours to days later.

CPR saves lives. However, consider the life you are “saving.” In this case the patient’s very best hope was to return to the state we found her in: sick, in pain, and unhappy. Is this what you wish for your loved one? More importantly, is that what the loved one wished for him or herself? Really think about the importance of advanced directives like a Do Not Resuscitate form for your loved ones. Think about them for yourself when the time comes.

This stuff applies to you, whether you realize it or not. It may not apply right this moment, since you’re young and healthy, but one day it almost certainly will. If not for yourself, this may be applicable for a parent, grandparent, or sibling. Deal with these issues NOW. Accept their wishes. Think about the quality of life your loved one has now, and what that quality of life might look like after a resuscitation attempt. Don’t put them through painful, often futile treatments if they don’t desire it.

The Reality of Death

The bottom line: I encourage you to think about the reality of death. In America we do a really good job of ignoring death until it’s on our doorstep. Try to reach some comfort with the fact that you will one day die. So will your loved ones. You don’t have to dwell on it, but you also shouldn’t treat death like some remote possibility. It is an absolute certainty.

If your loved ones have taken the time to fill out a Do No Resuscitate, respect their wishes. They have taken the time to think through execute that document. They wish to avoid a continuation of their suffering, or a prolongation of a poor quality of life. If they don’t want to experience the trauma of resuscitation, don’t selfishly let your discomfort with death supersede their wishes for their own bodies.

The bottom line: if you ignore your loved one’s Do Not Resuscitate and say, “do everything you can” you aren’t doing them any favors. At very best you’re prolonging their battle with a terminal disease that will win. You’re prolonging their pain and suffering, and adding some additional complications, all so you can have a little, misplaced peace of mind.

Please consider the physical pain and suffering your loved one might be in when they execute a Do Not Resuscitate order. Do right by them and honor it. Even though it’s difficult, it’s probably the right thing to do.

More Information

Sometimes a Do Not Resuscitate is known by another name, or supplemented by one of these other forms. These include the MOST (Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment), MOLST (Medical Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment), or POLST (Physician’s Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment). Particulars vary state-by-state, but this article answers some common questions about DNRs. For detailed, comprehensive information speak to your doctor.