If you are stuck at home during the current COVID-19 crisis you have an awesome opportunity to try some new things and learn some stuff. Today I’m going talk about some of my favorite culinary endeavors: fermenting things. Here are six live-culture fermentation projects that don’t require a lot of money or active time, but yield awesome rewards and improve your self-sufficiency and sustainability.

This article contains affiliate links.

What is Fermentation and Why Would I Do It?

Fermentation involves the use of bacteria and/or yeast to accomplish a task like transforming one thing into something else, or preserving foods for periods of storage. Most of us are familiar with the transformational aspect in some way. Many of us have used yeast to transform flour, water, and salt into a loaf of bread, or a sweet, sticky liquid into an alcoholic beverage.

Some of you are probably aware of the preservation aspect, as well. Pickles are a good example (but not a great one; modern pickles are just dunked in vinegar, not fermented like they have been for most of human history): pickling vegetables through fermentation helps preserve them over the long winter. If you’re serious about longer-term self-reliance this should definitely be in within your ability.

Fermenting also gives you something really, really cool to share with your neighbors. As I’ve mentioned multiple times before (and written two, in-depth posts about) we are working very, very hard to establish rapport with our neighbors. The knowledge and skill to do some of this stuff can make you an asset among your kith and kin, your neighbors, your community. To borrow a credo from Integrated Skills Group, always be an asset.

I really enjoy fermenting foods, and have ever since reading Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation. I like being able to produce my own bread from raw ingredients. I like being the neighbor that barters with home-brewed beer and sauerkraut. I like being able to preserve vegetables when they are in abundance, because one day, they might not be. Most importantly, I just enjoy the process of transformation and enjoying the fruits of my labor.

Here are six fermentation projects you can get into. Each requires a different level of commitment. I have tried to arrange these in order from least complicated and least equipment demands to most complicated and expensive. One book that you may find helpful in addition to Cooked is The Art of Fermentation by Sandor Katz. In fact, I strongly recommend the print form of The Art for any person serious about the ability to preserve food without modern conveniences, chemicals, etc.

Sauerkraut

Believe it or not there is nothing more to sauerkraut than cabbage, salt, and time. Seriously – that’s it. The recipe is simple: add salt to finely chopped cabbage in an anaerobic environment and wait until it turns into sauerkraut. Salt draws liquid out of the cabbage. You compact the cabbage into a container, like a Mason jar, and weigh it down. So long as all the cabbage is completely submerged, lactobacillus that is already present on the cabbage leaves will begin converting it to sauerkraut. It takes ten days to three weeks to get it where you want it depending on a number of factors, not the least of which is the temperature where you’re fermenting (warmer usually equals faster).

This converts plain cabbage into something wonderfully flavorful. It also preserves it. Fermented, your cabbage (which is loaded with nutrients and fiber) will last deep into the winter; refrigerated it will easily make it all the way back ’round to spring. Here’s what you need (besides cabbage and salt): a vessel, a weight, and some sort of cover for the jar. You can improvise every bit of this, or can buy a sauerkraut kit online. We have this one and use it heavily. If you get really into sauerkraut, you can buy a crock – a much larger, wide-mouth container – with weights. We don’t have a crock but as much sauerkraut as we make, we should. As a cover for the container we use cheesecloth.

Sourdough Bread

Sourdough is, apparently, the new hotness during COVID-19. No one in our community wants to admit their part of anything that’s popular, but I’ll fall on that sword: I’m making sourdough now, like a lot of yuppies and soccer moms and people that six weeks ago were “gluten sensitive.” I have made it before but haven’t in years. For some reason – despite having zero social media and no cable TV – I am compelled by the zeitgeist to make it now. There is preparedness value in knowing how to do this, too. As you may have noticed if you’ve been to the grocery store, yeast is hard to find. People are baking like crazy right now. Being able to generate your own yeast, more or less from thin air, is a pretty cool skill to have.

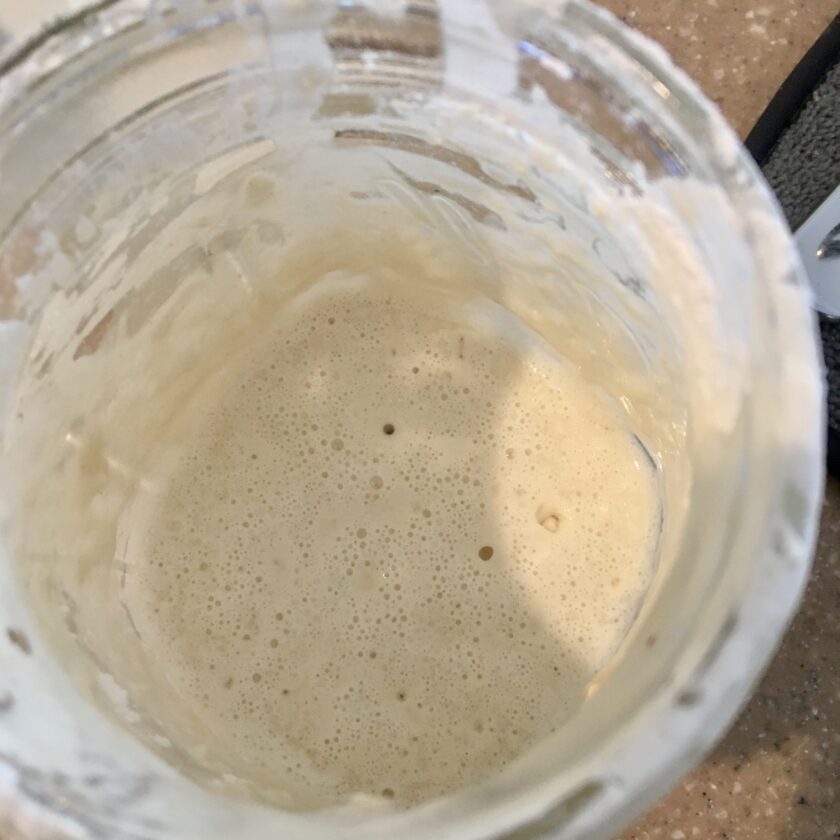

You don’t need to buy a single damn thing to get this going, as long as you have some flour. Mix equal parts flour and water (start with a cup or so of each). Place in an open-topped container on your kitchen counter. Though I generally prefer a wider vessel for more surface area, I used a Mason jar this time and it’s working beautifully. Every 24 hours throw out half of it, and replace it with half a cup water, half a cup flour. Lather, rinse, repeat until it starts to get bubbly and have a sour smell. Once you’ve made it, find a good sourdough recipe.

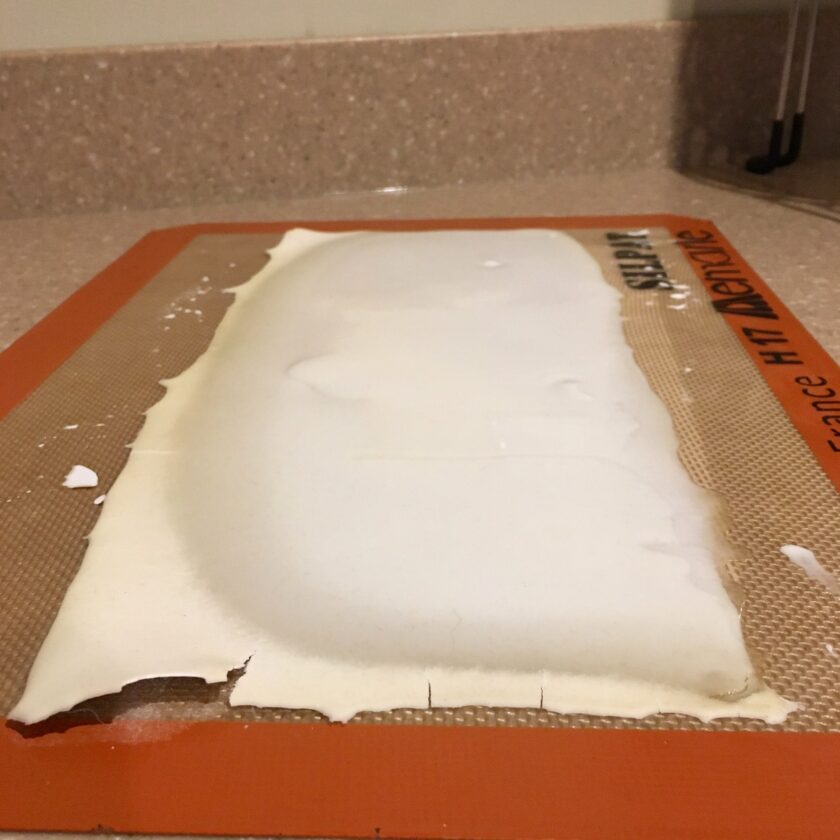

You can store your extra yeast, too. Trust me – you’re going to want to feed this thing daily (or twice daily) for only so long. One thing you can do with some of the starter you throw out each day is dry it. We dry it on a Silpat. Waxed paper would probably work fine, too. It takes several days but once dried fully you can store this – and the viable yeast it contains – for a long time.

Yogurt

Yogurt is the thing I have the least personal experience with. I have made yogurt and I have made kefir, but neither recently. Both require nothing more than milk and some bacteria, and maybe a thermometer. You can purchase yogurt starter online, or use just a bit of store-bought yogurt as you starting culture. The jar of yogurt in the featured photo is one a neighbor gave us in exchange for some beer we gave them.

Mead

I began brewing with mead. Not because I love mead, but because mead seemed pretty non-intimidating. Mix four pounds of honey with a gallon of warm water, add yeast (and little yeast nutrient if you want to get fancy), then watch and wait. Seriously – that’s it. Making mead is fairly easy compared to making beer, and that’s probably why a lot of people start with mead. I don’t think you need to start with mead but if you’re on a strict budget – or really like honey-wine, have bees and an abundance of honey, etc. – go for it.

Unfortunately I don’t really care for mead enough to make a bunch of it, but I do think it is an awesome way to dip your toe into fermenting beverages. Amazon has a 1-gallon mead kit for under $15 that will get you on your way. If it turns out you love brewing you’ll want a bigger and better setup, but this is a really cheap, easy way to find out if you like it.

Kombucha

Here’s the deal: I’m not one of those people who subscribes to kombucha as a cure-all. I do really, really enjoy the taste, though, and I might know why. I don’t want this to sound like a sob-story, but I didn’t grow up with a lot of money. At least three nights a week throughout my childhood we ate pinto beans for dinner. Not because my parents were preppers or vegans or some other product of abundance. It’s because that’s what they could afford to feed us for supper. One thing I’ve begun to notice is that bland staples like that call for strong accompaniments – hence the reason nearly all my family members of my dad’s generation will eat a slice of raw onion or nibble a hot pepper or drink a glass of buttermilk with his pinto beans.

I think that’s why I really like the vinegary tang of kombucha. If the probiotic qualities of it do something good for my gut flora, then great! If not, then great! I’m not going to type out how to make kombucha, but it isn’t hard. After we ferment our basic kombucha – which is nothing more than black tea, water, and sugar, with a giant, floating matt of bacteria on top of it – we usually do a second fermentation and add some fruit. My personal favorite is blueberry and vanilla, we we also did a raspberry one recently that may be the best kombucha I’ve ever had.

Getting into kombucha isn’t all that expensive. You can get a full-on kit from Amazon for around $50. I’ll be honest, though: if you have a 1-gallon, wide-mouth jar, tea, and sugar, all you really need is a SCOBY. You can order a SCOBY from Amazon (we successfully used this one to restart our kombucha after our move) for around $15.

Beer

It’s hard to go wrong with making alcohol. Even if you don’t drink it’s still a very valuable commodity. We don’t drink a lot but we still brew beer because it’s so popular with our neighbors. Beer has given us an “in” with a lot of the neighbors and a direct exchange with some others.

Delving into the world of beer brewing is surprisingly easy. I recommend starting out with extract brewing. This is somewhat simplified brewing with a bigger margin for error than the alternative, all-grain brewing. After brewing for several years, we just started doing all-grain brewing. Don’t think that extract brewing isn’t brewing – it absolutely is.

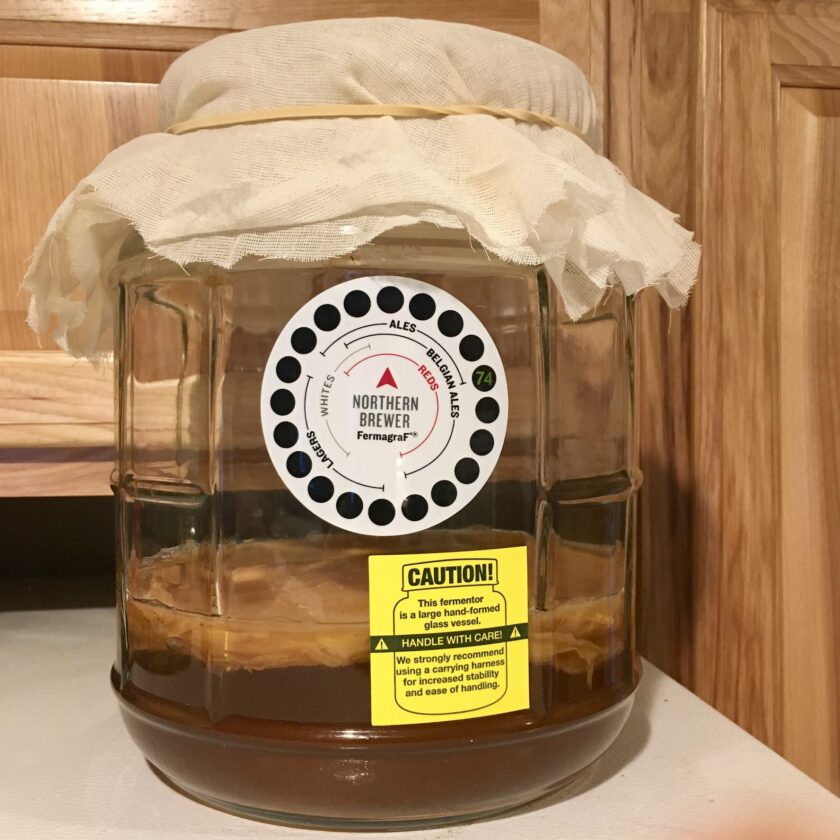

We began with the Deluxe HomeBrew Starter kit from Northern Brewer. We have added a couple things (like wort chiller and a propane burner) but this kit is completely, 100% usable for extract brewing as-is (you will need a few more things if you’re going directly to all-grain. If you’re looking for a similar setup for a little less money, Northern Brewer also offers a basic home brew starter kit that used plastic buckets as fermentation vessels instead of glass carboys, for a savings of (at the time of writing) $60. Various 1-gallon kits are out there, too, but generally, I don’t recommend them. There’s something about beer that makes it really difficult to scale down to a gallon and still get a decent product.

Closing Thoughts

I doubt most of you are going to go as “all-in” on fermentation stuff as we have (and I still feel like we have a long way to go). I hope some of you adopt some of these skills, though.