The Instructor's Burden

Lately I have been seriously thinking about the instructor's burden: the duty an instructor of life-and-death topics has to his or her students.

My Instructional Background

I generally don't like to tout my own experience, but I do want to briefly establish my credibility as an instructor. For four years and ten months my full-time job was teaching special operations personnel. I taught everything from basic patrolling to firearms to advanced topics and tradecraft that I can't get into here. I taught on the lecture platform, and in the field and on the range. To this day I am still loosely involved with this organization and teach for them occasionally. After that stint I went into business for myself. I made quite a comfortable living teaching special operations, federal law enforcement, and intelligence personnel.

I have personally instructed Rangers, Special Forces soldiers, Navy SEALs, Marine Raiders, and conventional military personnel from all branches. I have taught officers and agents from the DEA, DHS, NCIS, US Marshal's Service, US Secret Service and some oddballs like the Office of the Senate Sergeant at Arms and IRS Criminal Investigation. I have also taught classes for a couple of agencies that NDAs prevent me from mentioning. You can probably figure them out. I have received glowing praise and repeat business from all.

The Instructor's Burden

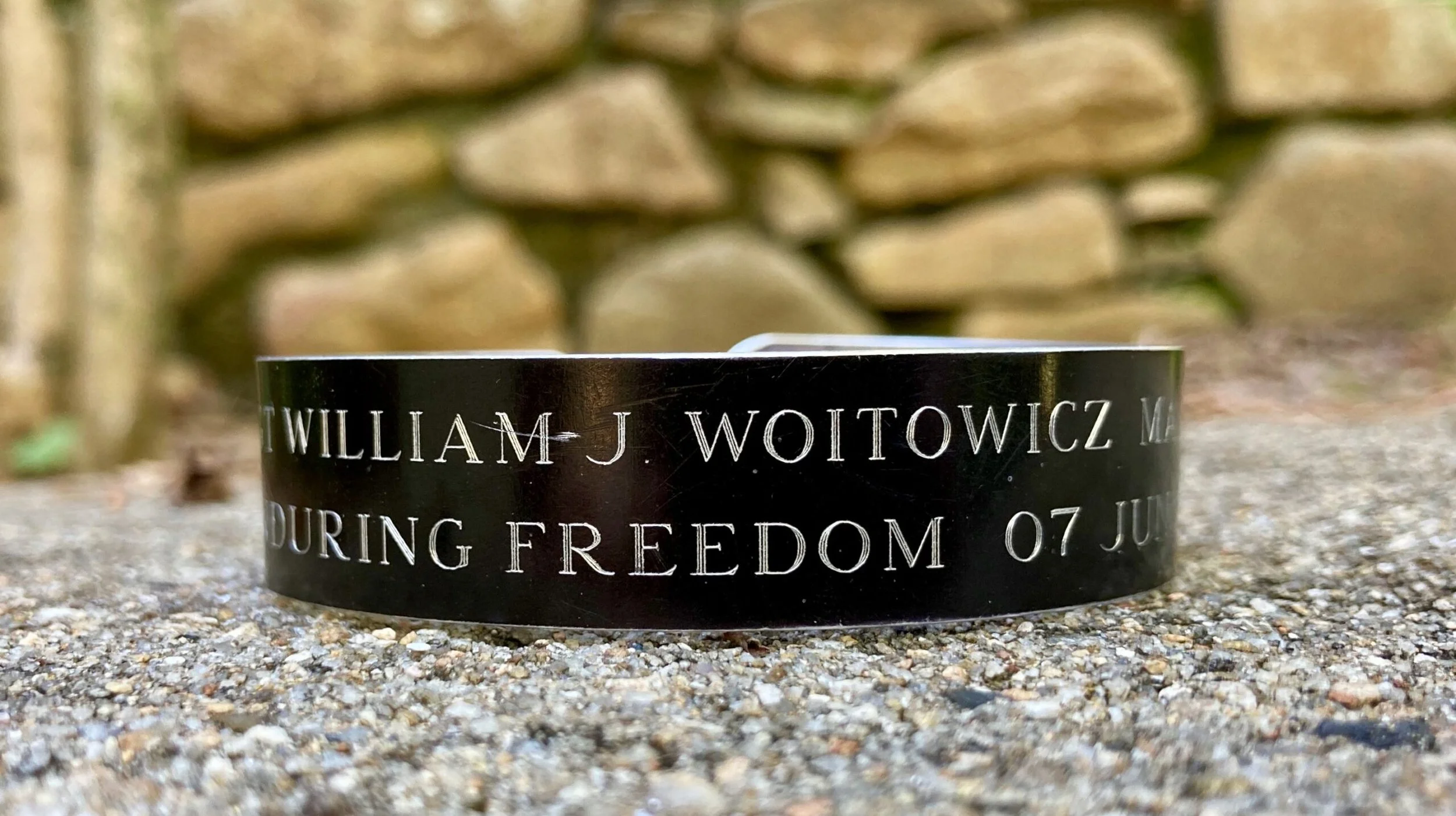

I began teaching professionally in February 2010. Fourteen months later, in June of 2011 I lost my first student. His name was William J. Woitowicz. Bill Woitowicz volunteered to be a Marine. He volunteered again to be a special operator. He volunteered a third time to deploy to Afghanistan as a combat replacement - filling the role of someone who had already been wounded. Shortly after arriving in Afghanistan he was killed in combat.

I had been very closely involved in Woitowicz's ITC class. I had been a cadre member for his team off and on throughout their class. I knew him personally, and had even run into him and a few of his teammates at bars in town occasionally. After his death I spent a lot of nights asking myself these questions: was there anything I could have done better? Did I do or fail to do something that got him killed? I honestly don't believe so, but the nature of life-and-death instruction demands such questioning and soul-searching.

The question that subsequently kept me awake at night was, "could I look his mother in the eye and tell her that I gave him 100% of myself?" In Woitowicz's case I could not answer that question affirmatively. I certainly worked hard. I don't believe I slacked during his course. I took it seriously. However, I didn't yet have the foresight to self-audit and ensure I did everything I possibly could.

I lost more students over the years, in combat and training accidents back at their individual commands. In each case, though, I was able to look myself in the mirror and know there isn't anything else I reasonably could have done differently.

Your Duty

I hope you never experience the loss of a student. If you do, you will want to be able to say that you gave him or her 100% and nothing less. You likely will never have 100% of the information, even if you are a lifelong student yourself. But you should give the student 100% of what you are capable of.

I know many of you are giving your all on the instructional platform. Some of you are not. I have certainly been disappointed with some classes I have taken, and some of you training junkies probably have, too. This is something I rarely see addressed in instructor development courses I have attended, but if you teach skills upon which lives depend, you owe it to your students to ask yourself that question now, pre-incident, at the end of every training day: did I give my students 100% of what I am capable of giving?

Here are a few questions you can ask to self-audit yourself.

Have I prepared myself for class? If you're opening the PowerPoint ten minutes before class starts, you probably haven't prepared adequately. You should review your material ahead of time, and know more than what you are directly presenting to the students. If you're in your first few years of instruction or are teaching in a very narrow time slot, you should be rehearsing your class. You should carefully consider the time you are spending on your curriculum outside of class and assessing its adequacy.

Being prepared also means being well-rested, fed, watered, and ready to instruct; you shouldn't start your day thinking about lunch or your first smoke break. You should be physically and mentally able to perform what you are asking of your students.

Am I prepared for student questions? It's hard to anticipate student questions if you haven't taught before, but you should know the material inside and out before you begin teaching. You can try by "murder-boarding" (rehearsing) the class in front of someone else. if you can't do that, write down your own questions that come up in your rehearsal.

Am I willing to stay late or come in early? The best instructors I have learned under weren't clock-watchers. They were willing to come in nearly. They were willing to stay late. They were willing to spend the time needed (within reason, of course) to get the student where he or she needed to be.

You should also be assessing your performance after class with introspection and honesty. Was the class time well-spent for the students; was the class on-topic, or did sidetracks and war-stories consume significant class time? Did each student get his/her time and money's worth? What could you do better?

Closing Thoughts

I hope this didn't come across as emotional - it wasn't intended to. This is something we don't talk about very much. If you're an instructor of life-and-death skills, you should really be thinking about your duty to your students, and spending at least a little time self-auditing and ensuring you're living up to that duty.